Miriam Nekrycz recorded her testimony as a Holocaust survivor in her book Account of a Life, which was published in Brazil in 1995. The book opens with Miriam and Ben Abraham’s trip to Poland and Ukraine, after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Along the railroad from Warsaw to Kiev, she could remember the names of the cities that had once thrived with Jewish life for centuries.

The couple visited Auschwitz, Treblinka and Majdanek in Poland. In Auschwitz, Ben Abraham could not help crying at the spot where he was parted from his mother. In the area where Treblinka once stood, only the stones bore witness to the Jews who had been deported from the Warsaw ghetto directly to the gas chambers. The Majdanek camp now was so close to the center of Lublin that they could see it from the road; the Nazis had not had time to destroy it before the Red Army arrived.

The arrival at Luck triggers the account of Miriam’s childhood.

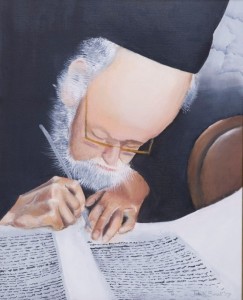

Life was good for the Jews of Luck in the 1930s. Her paternal grandparents had a cereal store; her grandfather spent most of his time studying the Torah while her father – the oldest son – managed the store with his mother. Two of their other sons had immigrated to Eretz Israel; one of the two daughters had married and moved to the United States.

Her mother’s family was also stable; the widowed grandmother had managed to raise the seven children running a shoe store during World War I. One of the sons had moved to Brazil after having lived a few years in Eretz Israel with his family.

The whole family attended Shabbat in a synagogue in the neighborhood of Wulka, where they lived. Although most of the time she was among Jewish relatives and friends, she attended a municipal school with Catholic children, where the teachers did not discriminate against Jewish children. However, she sometimes would hear Polish children shouting “Jews to Palestine.” She did not know what that saying meant.

In the winter of 1938-1939, her parents opened a new fabric store. Also her twin brother and sister were born around that same time. Those were happy times despite of some hardships. One day,the family’s maid simply threw hot water on one of the babies, who had to be treated for serious burnings. Apparently, she had done that on purpose.

One day, Miriam heard the adults discussing the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany. Then, all of a sudden, the war began for their family; their town was bombarded by the Germans. Her father sent the family to a smaller town where they would be safer. Another day, news came about the Soviet-German pact; Poland would be split in two and they were on the Soviet side of the occupied territories.

Miriam’s family came back to Luck and life seemed normal again. Meanwhile, thousands of Jewish refugees crossed the Bug River in order to flee from Nazi-occupied Poland. The Jewish community received many of them in their houses, and a young lady moved in with them. Her name was Hella – she had fled with her sister, but had gotten separated from her during the trip. Although Miriam’s family treated her as their own daughter, Hella frequently cried for her parents and sister.

Soon the Soviet soldiers and public officers arrived in Luck and began to impose their rules on the occupied territories. At school, religion classes were abolished, as well as Polish lessons; now Ukrainian and Russian were the languages children would learn. Indoctrination of patriotic values was also very strong; Stalin was portrayed as a loving father, whose glorious acts of courage were exalted in songs and movies the children watched.

Miriam’s parents decided to close the store, in order to avoid losing their goods. Since the Soviet soldiers wanted to buy everything using the old Polish currency, which had lost its value, selling it meant losing it, and not selling it was dangerous.

The Jewish religious school was shut down and the building was transformed into the “Palace of the Pioneers.” The pioneers were children and youth who had sworn to be always ready to serve Russia. In the “palace” there was no distinction among Jewish and non-Jewish children.

Those were dangerous days, especially for the wealthy; the Soviet secret police invaded their homes, confiscated everything, arrested the men and sent them to Siberia. One day they came after Hella, for she had enrolled to return to Nazi-occupied Poland. The Russians decided to arrest all the people that had enlisted in the return program and deport them to Siberia. Miriam’s father managed to get her back home, but she did not stay with them for long. Soon afterwards, the Soviet officials came again, and she was put on a train. They never saw her again.

Since they could no longer run their store, Miriam’s father got a job at a snack bar. At the same time, the once haughty and well-to-do Polish public officers no longer lived in the beautiful neighborhood of Urzendniczej Kolonij; Soviet public officers now lived in their instead.

The spring of 1941 seemed happy for Miriam, until June 22nd. Little Miriam woke up in the middle of that night because of an explosion. Germany had invaded Soviet-occupied Poland and everybody was in a panic, including the Soviet officers, who began to flee back to Russia with their families.

Miriam’s family had no place to go. The Germans threw incendiary bombs all over the neighborhood and everything was on fire. As the people fled their homes and gathered by the River Styr in order to escape the fire, German planes would fly over them to shoot them.

They fled to a village that had not been bombed, but the Germans arrived in that village three days later. Thus, they were forced to return to Luck together with a multitude of refugees, only to find out their house had been reduced to rubble. They then decided to move into her grandmother’s home, sharing the house with other relatives.

The Nazis soon began to persecute the Jews, aided by volunteering Ukrainian militiamen. All the men in the city were summoned to forced labor on the first Sunday of the Nazi occupation. Around 2,000 Jews presented themselves – never to be seen again. On the following Thursday, a new decree summoned all Jewish men, so Miriam’s father and uncle went to the appointed place from where they were supposedly to be taken to work, along with 3,000 other Jewish men – also never to return. Her mother was left with the four children: Miriam, Moniek and the two baby twins.

Day after day, new decrees came: Jews had to wear a yellow star; Jews could not walk on the sidewalk; Jews could not go into public places; Jews had to uncover their head when they saw a German soldier. Those who did not follow the rules were to be executed on the spot.

Around 25,000 Jews lived in Luck before WWII. At the beginning of the occupation, 5,000 Jews were taken by the Germans. Those who stayed were mainly children and women.

Miriam says she suddenly became an adult, trying to help her mother support the family of four children. She exchanged household utensils for food, but the children were always hungry. Meanwhile, new decrees came for the Jews: they were supposed to hand in any valuable objects that they still owned to the Judenrat, a kind of Jewish council that had been created by the Nazis – to which, according to Miriam, upright and honorable Jews never volunteered. Many Ukrainians took advantage of the situation and looted Jewish homes. Their home was also looted by a Ukrainian who pretended he was going to bring them some food.

The Russian prisoners also suffered at the hands of the Nazis; indeed, they were made into a public spectacle that even the Jews would feel sorry.

Curiously, many soldiers of the Wehrmacht lived in a building beside their home, but they did not molest the Jews. One night a German man invaded their house; little Miriam and her cousin jumped through a window and fled into the building of the Germans. Although they were forbidden to leave their home during the night, the German soldiers did not harm them, but rather came in the house and expelled the invader.

Following allegations of a Polish shoemaker who had lived alongside the Jews (a man who made his living from the Jewish community for several years), the Germans now came to the house looking for leather. This Polish shoemaker had become a spy and insisted that Miriam’s family had hidden leather in their house. The Germans came in several times. Although even the roof was removed in the search, nothing was found. It seemed the shoemaker expected to “inherit” what belonged to the Jews, just like many of their Polish and Ukrainian neighbors.

In contrast, a Protestant pastor that lived in the same area never tried to get anything from them wrongfully. Instead, he would give them some of the vegetables he grew in his yard. He also agreed to hide Miriam’s aunts’ sewing machine in his house, in order to prevent it from being confiscated.

Continue reading: Deportation, Loss and Hiding